Meet the teenagers making tiny homes and green roofs to protect communities from climate change

- Jon Shieber

- Oct 24, 2022

- 11 min read

What do you imagine when you dream of a solution to the laundry list of issues augmented by the climate crisis? For 16-year-old Bouchra Geagea, that dream is green roofs across her country of Lebanon and worldwide. For 16-year-old Renee Wang, that dream is sustainable tiny homes to help the unhoused.

Wang and Geagea are two of the 100 fall 2022 Rise Global winners. These winners were selected from a pool of 120,000 15- to 17-year-olds working to create a better world. This is the second cohort of Rise, a program built in partnership by Schmidt Futures and Rhodes Trust.

The program is the anchor of a broader $1 billion commitment by Eric and Wendy Schmidt to identify, develop, and support global talent working in the service of others. The inaugural and fall 2022 winners come from 69 countries, each of them aiming to mitigate a local or world issue. The issue of climate change reverberates throughout the projects, whether it be using fish waste to clean up heavy metal pollution or creating a sustainable gummy vitamin that combats anemia.

Bouchra Geagea, a high school student in Dbayeh, Lebanon, wanted to show how small climate actions can also have a considerable impact. For her project, she implemented green roofs to educate her community on the role of citizens in mitigating global warming.

“I already knew about the issue, and am very passionate about helping the environment,” she said in an interview with FootPrint Coalition. “I do live in the city but constantly go to the mountains. I’m surrounded by nature most of the time.” Spending her weekends in the Bsharri mountains is what got Geagea passionate about climate change.

Participating in Model United Nations has also increased her knowledge about worldwide issues and exposed her to the urgency of the climate crisis.

“My hope is that people wake up and realize how major this issue is and start collaborating with each other and helping each other. We can solve this issue altogether because it's still not too late,” she said.

When Geagea first registered for Rise, she didn’t know much about green roofs. Later research revealed social, environmental, and climate benefits. “By implementing green roofs, families, and neighbors would be able to interact with each other, distract themselves from their problems, and focus on being happy, and taking care of the environment,” she said. While it’s fun, it also benefits the Earth by emitting lots of oxygen and allowing community members to grow their own produce.

In other cases, green roofs can act to heat the buildings they’re built atop, she said. According to the National Park Service, the benefits go both ways: cooling and heating a building. In comparison to traditional roofs, which absorb heat, making it difficult to cool buildings, the green roof not only reduces the temperature of the building but through its extra layers, serves as insulation. The reduction in cooling loads can also help reduce greenhouse gas emissions. According to the service, adding plants and trees to urban landscapes increases photosynthesis, reducing carbon dioxide levels produced by vehicles and industrial facilities, and as Geagea said, increases oxygen levels, invaluable for human health.

However, because she worked on a limited budget, she had to implement her green roof on a more modest scale.

She pointed to the economic crisis currently going on in Lebanon, which according to Reuters, was brought on by unfettered post-war spending and political paralysis. “People are not able to buy their necessities, so how about buying plants?” Geagea rhetorically asked. “So I came up with the idea to fund the project myself.”

With the help of her father, she was able to connect with a local florist to build a green roof in her neighborhood. Prior to the implementation, she went door-to-door educating her neighbors about the project and climate change.

“I explained to them what they [green roofs] are, the benefits, and I walked them through the process,” she said. “I told them that they wouldn't have to pay anything, so they would understand that money was not an issue in taking part in this project.”

The response she received from her community shocked her. “I was actually very surprised,” she said. “When I was telling them about my project, I thought they would not interact much with the idea, but surprisingly, they were excited about it. Everyone that I asked to take part in my project agreed. When I came back to check up on the plants, they were taking care of them, happy about it, and excited, so that was truly amazing.”

While Geagea wishes that the project could be done on a larger scale, she says that success on the small scale indicates how successful a larger project would be if it receives investment.

“If I had more funds for this project, I would work on founding an NGO (non-governmental organization) that seeks to spread green roofs all over Lebanon,” she said. “This NGO would use the help of engineers to make sure roofs are able to support green roofs and volunteers to help organize this project throughout different regions of Lebanon, allocate funds, get sponsors, and stay updated on the progress and efficiency of the project. With these funds, I’d be able to greatly increase the effects of my small-scale projects and their advantages, in addition to being able to afford various types of vegetables and fruits.”

On larger scales, green roofs have a world of advantages, one being economic benefits and energy savings. A valuation study at the University of Michigan compared a 2,000-square-meter conventional roof and a green roof, looking at a range of reported benefits such as stormwater management, improved health benefits due to reduced pollution, and energy savings.

They found that over its estimated lifespan of 40 years, a green roof would save about $200,000. Nearly two-thirds of this bounty would come from energy savings. Geagea hopes to expand her project to reach milestones like this.

The project also relates to her future ambitions. “I want to be a lawyer when I grow up,” she said, highlighting her passion for community involvement.

“I just want to help people realize that we should not always depend on the government to help us out of problems or climate change. We should sometimes try to take the initiative ourselves as citizens of a country. That's one of my main goals right now: to make people understand that it's so essential to help the environment. It’s a duty, not an option, because we all live on Earth. It is all of us, our home.”

Geagea says she looks up to every single person joining the fight to mitigate and adapt to climate change. She says that even though many people may not have the financial means to go sustainable, her biggest motivation is people doing their best.

To 16-year-old Californian, Renee Wang, fighting climate change means addressing intersectional problems sustainably. And for Wang, the twin problems of climate and housing are at the top of her list.

For her Rise project, she designed a sustainable tiny home aptly named RUBIX, after its Rubik’s Cube-inspired design. Taking after other activists reimaging shelters as tiny homes to support the independence of unhoused individuals, these homes could work as a stepping stone to getting these individuals back on their feet.

When many shelters are over-packed large communal rooms, it can become dehumanizing to the point where some people would rather sleep on the street than in a shelter, Wang said in an interview with FootPrint Coalition.

"So I really wanted to create something that was not only affordable, sustainable, and accessible, but would also offer a fully independent lifestyle and privacy,” Wang said.

She wanted to give unhoused people “the ability to call something a home, rather than just a place to sleep or a shelter.”

Homelessness as a passion for her originated in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“When we were going through lockdown, buying masks and personal protective equipment, my family and I thought, it’s so difficult to get your hands on masks and other supplies, that it must be even more difficult for those living on the streets,” she said. “So, we really made an effort to make sure the people in my local community were being taken care of.”

They made homemade face shields and delivered care packages equipt with supplies like disinfectant wipes and hand sanitizer.

During that experience, Wang was able to speak with people living on the streets. Listening to their personal stories allowed her to understand the difficulties of homelessness and what got them to that point. The uniqueness of their stories and their resilience and kindness inspired her to create a blog.

Titled “Stories of the Streets,” the blog archives Wang’s conversations with unhoused individuals and updates readers on the progress of her tiny home project. One post entitled “Johnny’s Story,” tells the story of an unhoused man in Chicago who fell into his situation due to a cycle of parental abuse and depression, that spiraled after his partner passed while delivering and his mother soon after. He remains outside because of what he says is overpopulation and bedbugs in Chicago’s shelters.

“At that moment, I really recognized the humanity and resilience of people on the streets,” Wang said of her conversations. “I really wanted to spread their personal life stories so more people could be inspired or could be enlightened to the real situation of homelessness.”

Back in California, she learned that “the shelter system wasn’t necessarily the most effective.” Aside from crowded spaces, discrimination and lack of accessibility played large roles. Talking to local council members opened her eyes further to the reality, and the work being done behind the scenes.

Wang is a competitive golfer and on her trips, she is able to see that the issues in California exist across the nation. The admirable work of those working to pass better legislation bolstered her inspiration.

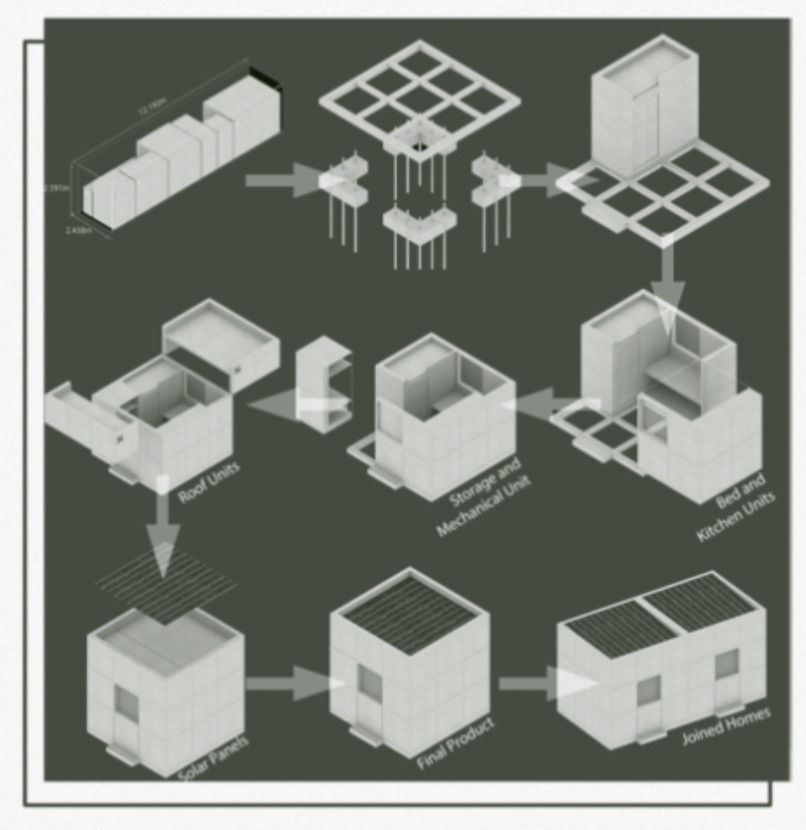

In creating RUBIX, she was inspired by the modularity and flexibility of a Rubik’s Cube.

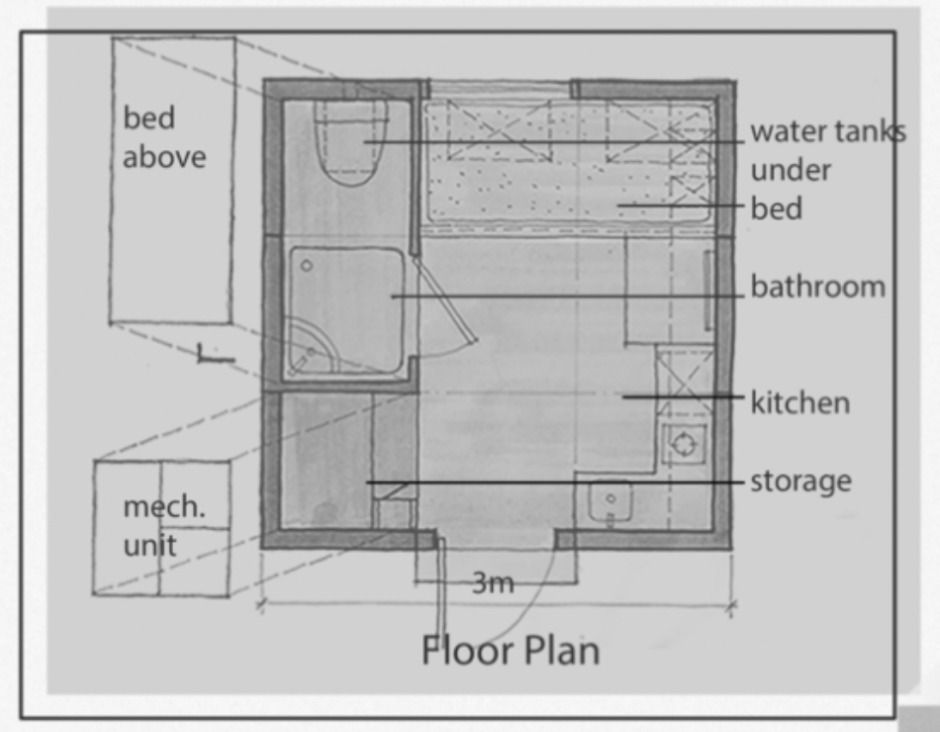

“I really wanted something that could be able to fit inside a storage container and something that could be easily transported,” she said. “I tried to imagine a space that could contain all of the necessary functions of living, for example, a private bathroom, a kitchen, and a bed or two, that was in the smallest, most compact space possible.”

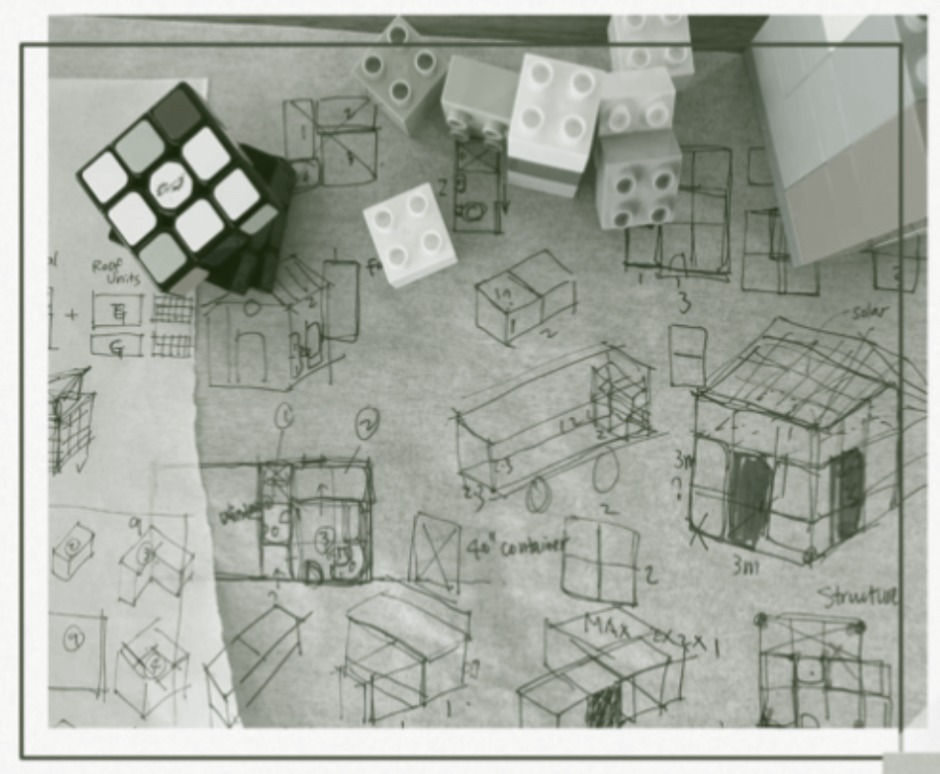

She made pages and pages of physical sketches and digital drafts. She even has a 3D model, an animated version to fit the pieces together, and is currently working with professors at the local college to build a life-size prototype. Working with the professors has allowed her to edit and pin down specifics of her design. Connecting with Rise, she says, will help her with resources and design improvement.

This is how RUBIX works:

The home itself will be made of recycled plastics and bamboo for its flexibility and how easily the grass flourishes. Ten pieces fit together, snapping in place like a storage container, to form a modular, deconstructable space. Each piece has a function, whether it be a bathroom or kitchen.

According to Wang, it can be installed on-site in a likely, shorter time than the conventional tiny homes cities are implementing, and be transported a lot quicker. But the main difference between RUBIX and other tiny homes, she says, is the sustainability aspect.

“The 100% prefabrication eliminates all construction waste,” Wang said. “Renewed and recycled materials decrease the carbon footprints. Off-grid solar and plumbing systems lower the cost of electricity and city line connections.”

The RUBIX tiny home runs entirely on solar energy, providing at least 13 kilowatts of energy daily, given the average San Diego sunshine. For context, one kilowatt is enough to vacuum for an hour straight or wash 12 loads of laundry.

A single solar panel can be tilted to best fit the direction of the sun, ideal for a home that moves around, Wang said. In addition, it's connected to a mechanical box with a battery that runs heating, cooling, cooking, and everything necessary for daily living. Wang underscored the importance of off-grid living, from the vast decrease in energy consumption to how affordable and accessible the concept is compared to conventional living and traditional shelters.

Constructing a life-size prototype will cost about $50,000, she said. If mass-produced the cost would be much lower. At present in California, the government is paying over $50,000 per year per bed in the shelters; a cost that does not include a one-time massive property investment cost.

Moreover, in Los Angeles, for example, even if every unhoused person was to sleep in a shelter, there are only enough beds for a third of them. According to the L.A. Homeless Services Authority, sheltering each individual would cost $657 million in the first year and $354 million annually after.

According to activists working to solve the homelessness and the housing crisis in Seattle, building traditional tiny homes can cost as little as $5,000 and $2,200.

Compared to these homes, Wang says RUBIX could be the smallest tiny home on the market that includes a kitchen and a bathroom within each unit. This offers further independence than the majority of tiny homes.

Wang was also inspired by products like airport sleeping pods and Boxabl’s folding homes – a self-described “instant house.”

A city in Germany is even testing these airport-style sleeping pods as homeless shelters.

Allowing someone a place to sleep at night, they are lit by the power of rooftop solar panels and can keep individuals safe from the cold and from attacks. The snow of Germany is unheard of in California, where Wang lives, but according to her research, the insulation and heating of RUBIX can survive even the temperatures of Alaska.

“The final goal for this design would be to have it benefit the millions of unhoused people all over the world,” Wang told FootPrint.

She would also like it to benefit those who have endured major hurricanes like those in Florida and Puerto Rico, and other places dealing with major power outages. She got the idea for expanding RUBIX as natural disaster relief when she was on a service trip in Puerto Rico this summer, building houses in the wake of Hurricane Maria.

“Being able to connect with the local community and those affected by Hurricane Maria really resonated with me,” she said. They made her want to find a solution. Hurricane Ian put more people on the streets, and unaffordable housing has exacerbated the issue.

Tiny homes may be a solution. After Hurricane Katrina, tiny homes helped mitigate housing loss. And after floods deluged West Virginia homes in 2017, they provided for either temporary or permanent living spaces.

In the future, Wang hopes to become an architect. As a kid, she always imagined it would be luxury high rises or skyscrapers that would prove her architectural ability and talent, but through this process, she’s learned that design is not necessarily about capturing luxury. “I think the biggest thing is being able to serve your community, both locally and globally, with design,” she said. “That’s the most important thing.”

“In terms of climate change it’s so important for the youngest generation to step up and reverse some of the damage that’s been dealt to our planet,” she went on. “It might be completely irreversible in my lifetime.” Sustainably housing her unhoused neighbors may be one way to make her community more climate resilient. With the same sentiment as Geagea, seeing young people in Generation Z passionate about and working to solve the climate crisis and other global issues gives her hope for the future.

“The world’s most important problems will be solved by the next generation of leaders,” Rise says. “Yet too often, the most brilliant people never realize their full potential for global impact. Either they are never discovered, become isolated at a young age, lack access to opportunities to develop their ideas, or face social and economic barriers.”

The benefits of Rise will last Geagea, Wang, and all the other winners a lifetime, as they will receive support throughout their careers. According to the program, “Rise is not an award for achievement nor a handout for life. It is a bet on potential, a beginning, not an ending and we are giving these 15-17 youth the opportunity to do the work throughout their lives.”

The next application cycle opened on October 18, 2022, and closes on January 25, 2023, at 16:59 Greenwich Mean Time. Young people ages 15 to 17 (as of July 1st, 2023) can apply on the Rise website. For applicants without access to mobile technology, Rise works with its partners on the ground to offer alternative pathways through paper applications.

Comments